Since the late middle ages it was a widely held belief that Grey Friar Berthold Schwarz from Freiburg had invented blackpowder around 1350. But today historians are certain that the invention took place much earlier and in a different part of the world.

Blackpowder technology seems to have evolved in ancient China, slowly spreading around Asia and via the Orient to Europe. The earliest record of blackpowder in Europe is given by Marcus Graecus in the 11th century and in England by Roger Bacon between 1242 and 1267.1)

Powder was produced in government-run powder mills or private enterprises. Marksmen and "Büchsenmeister" also made their own blackpowder and sometimes women, as documented in the accounting books of the Teutonic Order castle at Elbing (Elbląg in todays Poland)2), as well as parish priests or workmen3) made and sold powder as a sideline business.

The first evidence for the municipal powder mill of Hamburg is given in the Kämmreirechnungen (accounting books) of 1425 when the city council spend 177 ℔ 3 ß for app. 2.000 pounds of powder for Hamburg's involvement in the war between Holsatia and Denmark. The powder mill must have been established for some time by then.

In 1441 the Kämmreirechnungen record the destruction of the municipal fulling mill at Obermühle as collateral damage when the powder mill exploded. So it seems logical the powder mill, presumably powered by water, was also located at Obermühle. After this incident a new powder mill was build north of Alstertor, the cities gate at the river Alster. Another recording from 1549 notes 300 ℔ of outgoings for a powder mill at Millerntor. The amount of money spent suggests that a completely new mill had been build. 4)

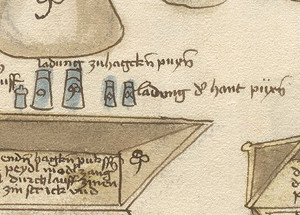

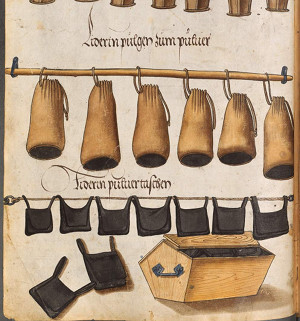

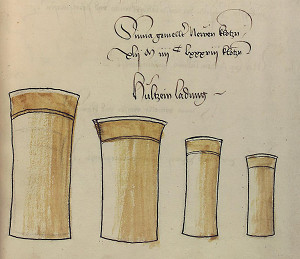

The marksmen of Hamburg were supplied with blackpowder by the city council directly or through their captain. But blackpowder was also a profitable merchandise. Big amounts of blackpowder were transported or stored in wooden casks,5) small amounts were stored and distributed to the marksmen in leather bags.6)7)8) In the field, riflemen carried their powder rations in powder horns9), powder flasks10) and possibly also loosely in leather pouches11) from which they scooped it out with a powder measure.12) From later times, bandoliers are known, belts with attached wooden containers that contained individually dosed powder charges. Precursors of these single charges could be the „Hulztein Ladung” (literally: wooden charge, wooden containers for single charges) from Landshuter Zeughausinventar7) or „ladung z hant püxs” (charges for handgonnes) form the war book of Eyb vom Hartenschein13). The equipment of larger stone rifles, bombarde or guns included wooden boxes in which powder, bullets and accessories were stored.

The marksmen of Hamburg were supplied with blackpowder by the city council directly or through their captain. But blackpowder was also a profitable merchandise. Big amounts of blackpowder were transported or stored in wooden casks,5) small amounts were stored and distributed to the marksmen in leather bags.6)7)8) In the field, riflemen carried their powder rations in powder horns9), powder flasks10) and possibly also loosely in leather pouches11) from which they scooped it out with a powder measure.12) From later times, bandoliers are known, belts with attached wooden containers that contained individually dosed powder charges. Precursors of these single charges could be the „Hulztein Ladung” (literally: wooden charge, wooden containers for single charges) from Landshuter Zeughausinventar7) or „ladung z hant püxs” (charges for handgonnes) form the war book of Eyb vom Hartenschein13). The equipment of larger stone rifles, bombarde or guns included wooden boxes in which powder, bullets and accessories were stored.

In the Bursprake (council's order) 1469, the Hamburg City Council announced that henceforth gunpowder could no longer be stored in the backyards. At the same time, however, the council obligated every citizen liable to military service to keep a sufficient supply of gunpowder and lead and to exercise particular caution when storing it..14) In 1537, the council forbade the storage of gunpowder packed in barrels in cellars, warehouses and on the streets of the city, presumably for fire protection reasons,15) and from 1594 all citizens had to store their gunpowder centrally in the citie's gunpowder magazine at Eichholz.16)

In the Bursprake (council's order) 1469, the Hamburg City Council announced that henceforth gunpowder could no longer be stored in the backyards. At the same time, however, the council obligated every citizen liable to military service to keep a sufficient supply of gunpowder and lead and to exercise particular caution when storing it..14) In 1537, the council forbade the storage of gunpowder packed in barrels in cellars, warehouses and on the streets of the city, presumably for fire protection reasons,15) and from 1594 all citizens had to store their gunpowder centrally in the citie's gunpowder magazine at Eichholz.16)

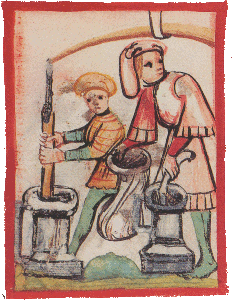

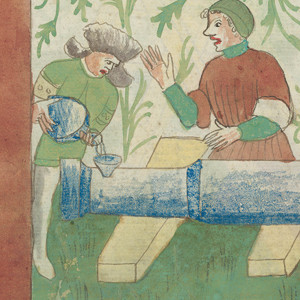

Often the gunners could not immediately use the powder they had been given, especially if its components charcoal, sulphur and saltpetre had separated again due to shocks during transport. Here they had to homogenise the powder, sometimes with the addition of alcohol or brandy, and then dry and grind it again.17) If it became damp during transport, it also had to be dried and painted in mortars or on grinding stone boards18) before use. If the powder was not available in the correct grain size, e.g. as priming powder or according to the requirements of the rifle, the gunners had to grind it down to the appropriate grain size himself. Each step in the process had to be carried out with great expertise and experience so as not to impair the ignitability and burning behaviour of the powder.17) In addition, the handling of black powder requires special care at all times due to its high explosive nature.

Historic Sources

„Liderin pulgen zum pulver” und „Lederin pulver taschen” Leather pouches and bags for gunpowder in Freyslebens Zeugbuch Kaiser Maximilians I. ca.1495-1500.8)

„Hultzein Ladung” wooden powder charge containers from Ulrich Beßnitzers Landshuter Zeughausinventar Fol. 47r ca. 14857)- „... item 5 lothebuchsen, item 400 gelote, item 2 grosse buchsen, czur grosten 48 steyne, item czur andern 120 Steyne, item 13 lederynne secke mit pulver.”

(Übertragung: 5 lead guns, 400 lead balls, 2 large guns, for the largest 48 stone balls, for the others 120 stone balls, 13 leather pouches with powder)

Enty in the Marienberg tessler book of the Teutonic Order for the commandery Schwetz of 12. März 1392.6)

References

- Strickhausen (2006): pp.. 47-48

- Schmidtchen (1977 a): pp. 48, 79

- Sixl (1897/98): Bd. II, p. 15

- Fiedler (1974): pp. 100-102

- Bolland (1960): 126.35

- Schmidtchen (1977 a): p. 39

- Beßnitzer (1485): Fol. 47r

- Freysleben (1495-1500): Fol. 70v, 296v

- Schilling (1478-1483) Bd. 1: Fol. 143

- Kriegstechnik (1420-1440) ZB Zürich MS. Rh. hist. 33b: Fol. 21v

- Schilling (1478-1483) Bd. 1: Fol. 32, 232, 243, 305; Bd. 2: Fol. 20

- Engel (1897): p. 232

- Eyb zum Hartenstein (1500): Fol. 276r

- Bolland (1960): 133,36-4, 134,16

- Bolland (1960): 126.35

- Bolland (1960): 146,91k

- Schmidtchen (1977 b): p. 114-119

- Kriegstechnik (1420-1440) ZB Zürich MS. Rh. hist. 33b: Fol. 34r

Currency symbols: ℔ talentum (Pound) / ß solidus (Shilling)

Text: Andreas Franzkowiak