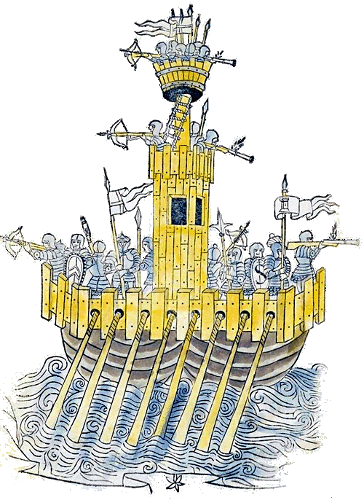

Like every free city, Hamburg had to secure its walls with a powerful city defence and assert its interests against its opponents. This was particularly important for the Hanseatic city, which depended on free trade, in the turbulent decades around the turn of the 15th Century. The security of the Hanseatic trade routes was threatened not only by highwaymen, privateers, pirates and beachcombers, but also by opposing princes and bishops who targeted the richly laden merchant trains and merchant ships with their crews. Without regard for the law, they captured ships, robbed their cargo and took crew members, mainly wealthy passengers or merchants travelling with them, hostage in order to ransom them for large sums.1) In particular, the Bremen Archbishop Albert (Albrecht) II broke secular and ecclesiastical law, which had been in force for over 200 years, by tolerating the capture of Hamburg ships on the River Elbe, from which he also profited significantly. He disregarded several papal orders to this effect, which finally led to a legal dispute before the Pope in Avignon in 1371, which finally ended successfully for the Hamburg City Council in 1387.2) All these threats prompted the allied Hanseatic cities on several occasions to equip armed ships Vredekoggen (literally: Peace cogs) to protect and secure the trade routes.3)

As in many other cities of the empire, the city guard and defence in Hamburg were not carried out by a permanent municipal army; rather, every inhabitant with Hamburg citizenship was obliged to perform these services. In the 14th Century, these services were organised through the offices, cooperatives and guilds. All burghers who were able to defend themselves had to provide an armament corresponding to their office and status, at their disposal and at their own expense. These could neither be lent nor pawned and had to be kept ready for use at all times. If a citizen did not comply with this obligation, he was fined and the city procured the prescribed equipment at his expense.4) By the way, this circumstance was also handled in exactly the same way by the council of the city of Lüneburg.5) Burghers who could not afford elaborate weapons, such as stall and cellar dwellers, should provide at least a good hand- or sidearm (short or long knife).4) Over time, this system organised by the offices led to numerous complaints to the city council due to unfairness in the number of riflemen to be provided, so that in 1458 the council divided the city guard and defence according to quarters and parishes. Citizens liable for military service were able to support themselves by providing equipped mercenaries or by paying protection money and making an entry in a special book (Verbittelbuch)4) being exempted from personal military service.6)7) The supreme command over the city guard, armies and Vredekoggen was mostly held by respected councillors.7) On 7 December 1576, the city council finally divided the ramparts into three units with their own muster stations.8) The city guard in Bremen was organised in a similar way according to the four parishes, which were only restructured into companies in 1605.9) The guards themselves were often a source of trouble, for example, they repeatedly roamed the town drunk at night after their duty was over, firing their rifles and disturbing sleeping neighbours, whereupon the town council had to ban the guards from doing so on several occasions in 1666, 1667 and 1676 under threat of punishment.10)

The city itself was secured with a mighty city wall with towers and gates, which were constantly adapted to the new requirements of war technology. To ward off enemy raids, numerous streets in the city could be cordoned off with heavy chains. These were attached to a house wall at a height of about one metre and, if necessary, were stretched across the street by citizens obliged to do so and fixed to the opposite house wall. The harbour facilities on the Elbe, which were vital for the city, could be sealed off against enemy ships by floating barriers made of tree trunks. Later, pile barriers were erected on the dammed River Alster to protect against raids.11)

The first written evidence of firearms in the city's defence of Hamburg dates back to the 14th century. Initially, these new types of weapons were imported from outside: 1372 twe donrebussen (two thunder guns) and 1373 twe kopperne bussen (two guns of copper).12) In 1379 the city bought a large stone connon in Lübeck and imported two more from Flanders in 1384.12) From 1381 onwards, the city council employed a master gunner (magister bombardarum) to supervise, guard and care for the guns and firearms. In 1435, four, from 1440 three and from 1461 two marksmen were appointed for this purpose. The marksmen who also made rifles had to show a master craftsman's certificate for this purpose.6) Sometimes skilled personnel were also recruited from outside, such as the gunsmith Huusmann from Lübeck in 1379/1380..14)

Finally, in 1470, the city had the first larger guns made by a Hamburg brass founder.13)

A radical modernisation of the armoury can be recorded for the second half of the 15th century. In the Thomae-Bursprake (councils order) of the years 146415) and 148616) all hereditary citizens, pensioners and merchants as well as young brewers without their own inheritance and self-employed craftsmen were obliged to equip themselves with a hand gun together with the corresponding powder and lead instead of a crossbow during the prescribed military service.7)13) The next renewal of firearms is ordered in the Thomae-Bursprake 1550, according to which the old hakenbussen (hackbuts) from the compulsory stocks of the breweries now to be recast into the now more common helen haken (arquebuse types).17) For the practice of marksmen on firearms, regular shooting exercises were held in front of the city gates, as well as shooting matches, i.e. early marksmen's festivals. During archaeological excavations in 2013-2014 by the Archaeological Museum Hamburg, along the Kaufhauskanal in Hamburg-Harburg, the remains of a marksman's bird were discovered. On 10 August 1560, the first shooting match with cannons took place from the Spitalertor in the direction of the River Alster.18)

A radical modernisation of the armoury can be recorded for the second half of the 15th century. In the Thomae-Bursprake (councils order) of the years 146415) and 148616) all hereditary citizens, pensioners and merchants as well as young brewers without their own inheritance and self-employed craftsmen were obliged to equip themselves with a hand gun together with the corresponding powder and lead instead of a crossbow during the prescribed military service.7)13) The next renewal of firearms is ordered in the Thomae-Bursprake 1550, according to which the old hakenbussen (hackbuts) from the compulsory stocks of the breweries now to be recast into the now more common helen haken (arquebuse types).17) For the practice of marksmen on firearms, regular shooting exercises were held in front of the city gates, as well as shooting matches, i.e. early marksmen's festivals. During archaeological excavations in 2013-2014 by the Archaeological Museum Hamburg, along the Kaufhauskanal in Hamburg-Harburg, the remains of a marksman's bird were discovered. On 10 August 1560, the first shooting match with cannons took place from the Spitalertor in the direction of the River Alster.18)

Since 1425, the operation of a municipal powder mill in Hamburg has been documented in written source,13) and the city council obliged its citizens to keep a sufficient supply of gunpowder and lead.18) Later the council issued various orders about the storage of gunpowder at the marksmens homes, until finally in 1594 all citizens had to store it centrally in the municipal powder magazine at Eichholz street.19)

Around 1476, the city finally had a municipal arsenal set up in Niedernstraße. Here, guns and stone balls, and later also hooked rifles and lead balls were produced by the employed master gunsmiths for the city's defence. The first gun completed there in 1477 by Laurens Grave had a weight of 241 pounds and was named „slange” (Serpent).13) Further gun names have been documented from Hamburg: „apostol” (Apostil)12), „salvator”12), „tumeler” (Tumbler)13), „vogeler” (Fowler)12) and „scharpemetze” (Scharfmetze, a heavy cannon type)9). Smaller guns as privately provided equipment of the city's defence, however, still had to be made by local smiths and bronze casters or imported.13)

The citizens' arms and armour must have been in use for a very long time, because in the Thomae-Bursprake of 21 December 155020) the right honourable council felt compelled to appeal to the honour of its citizens and urge them to:

„Dewile averst de were na verlope der jare, wo men vor ogen sut, in veranderunge und ungebruke gekamen und et mit dem harnesche to dusser tidt eine vele andere gestalt heft dan in vortiden, so wil sich geboeren und van noeden sin, dat dejennigen, welliche de olden schwaren iseren hoede und darto gelikformigen olden ungebruklichen harnesch hebben, bi tiden to orem live einen guden rugge und krevet, ermeschenen und hoevetharnesch schaffen, ok sust oren harnesch ferdich und to mate maken laten, dat se, wanner men in deme harnesche naber bi naber up de welle gan edder susts tor were kamen und herschouwinge don mot, darmede vor mennere van frombden und frunden unbeschimpet bestaen und gan moege!”20)

(Since the weapons have undergone changes over the years and have fallen into disuse, and the armour of this time is of a very different design from that of earlier times, it is proper and necessary that those who still possess the old heavy iron hats and the old, obsolete armour that goes with them, should, at the proper time, procure a good rug, crevet, bracers and main armour, or have their armour made to fit their bodies, so that when they stand side by side in armour on the ramparts or go before the gate to the army show, they may be able to stand up in front of strangers and friends without being insulted!)

References

- Reetz (1969)

- Schrader (1908)

- Jörgen Bracker: Von Seeraub und Kaperfahrt im 14. Jahrhundert. pp. 6-35. In: Bracker (2001)

- Bolland (1960)

- Schmidtchen (1985): p. 296

- Gaedechens (1889): pp. 422-424, 527-533

- Gaedechens (1872): p. 1-8

- Zimmermann (1820): p. 491-492

- Kohl (1871): p. 83–87

- Sammlung der von E[inem] Hochedlen Rathe der Stadt Hamburg, (1763), pp. 231, 236, 330.

- Pelc (2003): pp. 46, 50

- Kämmereirechnungen der Stadt Hamburg: 1350-1400, 1401-1562

- Fiedler (1974): pp. 100-122

- Leng (1996): p. 313

- Bolland (1960): 53.9

- Bolland (1960): 83.6

- Bolland (1960): 134.15

- Weiss (2017): Bürgerwehr & Schützengilde. pp. 112-115; Archäologisches Museum Hamburg: Tagebuch #Ausgegraben: Neues Grabungsfeld, Neues Glück … – Teil 2, 11 Juni 2013 (offline)

- Bolland (1960): 133,364, 134,16

- Bolland (1960): 146,91k

- Bolland (1960): 134,13

Text: Andreas Franzkowiak

Photos: Citiie's Seal: Wolfgang Meinhart, Hamburg, Licence: GNU FDL 1.2